Treatment

Discover THE TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR lYME AND PANDAS

Treatment of Lyme Disease

Early Treatment

-

Many patients with early Lyme disease treated with short antibiotic courses (< 20 days) recover.

-

However, clinical experience and scientific literature both show that a significant proportion do not return to pre-Lyme health after such short courses.

ILADS Recommendations:

-

For patients with erythema migrans (EM):

-

4–6 weeks of doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime

-

≥21 days of azithromycin is also acceptable (especially effective against European Borrelia strains).

-

-

For non-EM early disease: treatment is similar to EM protocols.

-

For disseminated disease: longer courses or antibiotic combinations may be required.

Treatment Response and Persistence

-

10–20% of patients remain ill following antibiotic therapy for early Lyme disease.

-

The clinical course and treatment response should guide further management.

-

Follow-up is essential:

-

If symptoms persist, recur, or new symptoms appear, persistent infection should be considered.

-

Borrelia burgdorferi has demonstrated the ability to survive antibiotics in laboratory, animal, and human studies.

-

Current testing cannot confirm eradication of the bacteria.

-

Chronic and Persistent Lyme Considerations

-

Persistent infection and co-infections must be considered in patients with ongoing symptoms.

-

Extended antibiotic therapy may be necessary when the risk of untreated infection outweighs the risks of long-term treatment.

-

Risks of long-term antibiotics exist but can be reduced with careful management.

-

Providers should engage in shared decision-making with patients:

-

Options for therapy

-

Risks and benefits of treatment

-

Risks of untreated persistent Lyme

-

Relapse vs. Re-Infection

-

Patients may be repeatedly infected with Lyme disease.

-

Both relapse and re-infection should be considered when symptoms recur after treatment.

Patient-Centered Care

ILADS emphasizes:

-

Person-specific, individualized care

-

Careful assessment and re-assessment of the full clinical picture

-

Treatment decisions guided by both the initial presentation and the course of illness if symptoms persist or return

Lyme disease

(Borrelia burgdorferi s.l.)

First-line (conventional) antibiotic therapy

Regimens below reflect the 2020 AAN/ACR/IDSA guideline and CDC clinical pages; tailor to age, pregnancy, allergies, and manifestations. IDSA+1CDC

Early localized (erythema migrans):

doxycycline 100 mg PO BID × 10 days; or amoxicillin 500 mg PO TID × 14 days; or cefuroxime axetil 500 mg PO BID × 14 days. Azithromycin only if others can’t be used. CDC

Early disseminated—cranial neuropathy (e.g., facial palsy): oral doxycycline × 14–21 days. CDC

Neuroborreliosis (meningitis/radiculoneuritis): doxycycline 200 mg/day PO or IV ceftriaxone 2 g QD × 14–21 days (choose route by severity/enteral tolerance). CDC

Carditis (atrioventricular block/myocarditis):

Outpatient, mild: oral agents (doxycycline/amoxicillin/cefuroxime/azithro) × 14–21 days.

Hospitalized or high-grade block: start IV ceftriaxone, switch to oral when improving; total 14–21 days. Temporary pacing is rarely needed; conduction usually recovers in days. IDSAOxford Academic

Lyme arthritis: oral doxycycline/amoxicillin/cefuroxime × 28 days; if minimal response, consider 2–4 weeks IV ceftriaxone or a second oral course, then transition to non-antibiotic arthritis management if synovitis persists despite adequate antibiotics. AAFP

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP)

For a high-risk Ixodes bite, consider single-dose doxycycline 200 mg (4.4 mg/kg up to 200 mg in children) within 72 hours of tick removal if criteria are met (Ixodes species, engorged, in a highly endemic area, etc.). CDC+1

Persistent symptoms after treatment (PTLDS)

Prolonged or repeated long-term antibiotics do not show durable benefit and carry harm in randomized trials; management is supportive and symptom-directed. New England Journal of Medicine

Common tick-borne co-infections (treat concurrently if suspected/confirmed)

-

Anaplasmosis (Anaplasma phagocytophilum): doxycycline (adults & children) 10–14 days (covers possible concurrent Lyme). CDC

-

Ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia spp.): doxycycline for ≥5–7 days and ≥72 h fever-free with clinical improvement. CDC+1

-

Babesiosis (Babesia microti and others):

uncomplicated: atovaquone + azithromycin × 7–10 days; severe disease or intolerance: clindamycin + quinine; consider exchange transfusion for high parasitemia/severe hemolysis. Immunocompromised patients often need longer/more intensive therapy. IDSACDC -

Hard-tick relapsing fever (Borrelia miyamotoi): treat similarly to Lyme: ~14 days doxycycline (or amoxicillin); anticipate possible Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction. Evidence base is mostly case series. CDC

-

Bartonella henselae (cat-scratch disease; debated as an Ixodes co-pathogen): usually self-limited; azithromycin can hasten lymph node resolution; severe/disseminated disease requires specialist-guided combinations (e.g., doxycycline with rifampin), noting limited high-quality evidence. CDC

Clinical pearl: Fever with leukopenia and thrombocytopenia suggests anaplasmosis/ehrlichiosis; hemolytic anemia or parasitemia on smear suggests babesiosis. Co-infections can blunt response to standard Lyme therapy—treat all identified pathogens.

PANDAS/PANS

Definitions:

-

PANDAS = pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcal infection (abrupt-onset OCD/tics temporally linked to GAS).

-

PANS = broader, acute-onset OCD/restrictive eating with neuropsychiatric symptoms, infectious or non-infectious triggers.

Guideline landscape & controversy:

-

The PANS Research Consortium (PRC) published 2017 consensus treatment papers (Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychopharmacology):

Three pillars—

-

(1) treat triggers (often antimicrobials), (2) immunomodulation by severity,

-

(3) manage psychiatric/behavioral symptoms. Liebert Publications

-

The AAP 2025 Clinical Report provides a cautious, non-guideline overview and emphasizes limited evidence and careful differential diagnosis. Expect payer/policy variability and ongoing debate. AAP Publications

Conventional management (commonly accepted)

-

Treat the trigger/infection

-

GAS pharyngitis/sinusitis/skin infection: treat per standard pediatric guidelines (e.g., penicillin/amoxicillin; macrolide if true allergy). In severe, strep-driven, frequently relapsing cases, some experts consider secondary prophylaxis (practice varies; evidence low–moderate). PPN+1

-

Non-streptococcal triggers (e.g., Mycoplasma, influenza, SARS-CoV-2): manage per usual ID standards; the causal role is less certain.

-

-

Psychiatric/behavioral care for OCD/tics/anxiety

-

CBT/ERP is foundational; SSRIs and standard tic/OCD pharmacology as indicated, with careful titration (some children are medication-sensitive during flares). The Heartwood Program

-

-

Anti-inflammatory / immunomodulatory therapy

-

NSAIDs and short oral corticosteroid bursts are often used for flares.

-

IVIG (1–2 g/kg) or therapeutic plasma exchange (PLEX) may be considered for moderate–severe, function-threatening cases when there is a convincing immune-mediated presentation and inadequate response to the above. Evidence includes:

• a 1999 randomized trial showing symptom reductions with IVIG and PLEX in infection-triggered OCD/tics;

• a 2016 double-blind RCT of IVIG that did not meet its primary endpoint, though some secondary and open-label signals exist;

• newer observational reports with mixed results. Decisions are individualized, ideally in multidisciplinary care. PubMed+1PMC

-

Routine tonsillectomy is not recommended solely for PANDAS/PANS; consider only for standard ENT indications.

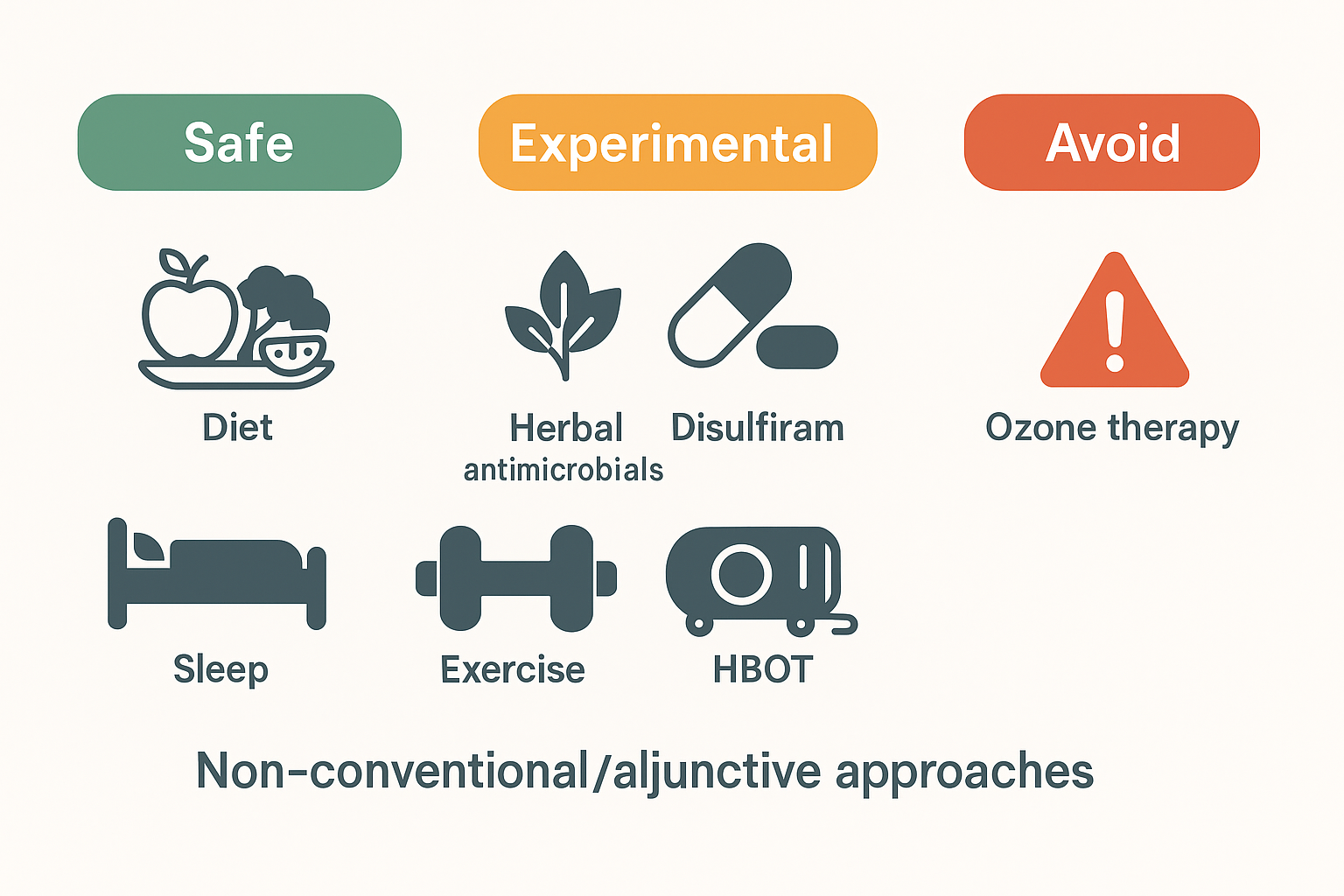

Non-conventional / adjunctive approaches (what we know)

Important framing: Many are unproven or have only in vitro or small, uncontrolled human data. Discuss risks, interactions, and cost with families; avoid substituting these for indicated antibiotics/immunotherapy.

-

Herbal/“botanical” antimicrobials (e.g., Cryptolepis sanguinolenta, Japanese knotweed/Polygonum cuspidatum, Artemisia annua): demonstrate in-vitro anti-Borrelia or anti-Babesia activity; robust clinical trials are lacking. Quality control and drug–herb interactions are concerns.

-

Disulfiram for persistent Lyme-attributed symptoms: mechanistic rationale and case series/pilot work exist; adverse effects can be significant; no definitive efficacy in large RCTs—use only with specialist oversight or in trials.

-

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT): not guideline-recommended for Lyme; evidence limited to small, uncontrolled studies; reputable reviews highlight approved uses vs. unproven claims.

-

Ozone therapy and similar “oxidation” interventions: the FDA states ozone is a toxic gas with no proven safe medical application; avoid.

-

Diet, sleep, graded activity, micronutrient repletion: low risk and sensible as adjuncts to manage fatigue, sleep disturbance, pain, and mood—not disease-specific therapies.